WOW! Really, wow!

The response to my most recent animation has been overwhelming, to say the least. I certainly had faith in it from the start, but my little Deinonychus sketch has quickly become my most liked, commented, and shared piece of media across nearly every platform I post on. Every few seconds for the last three days, my phone buzzes with another notification tied to heartwarming messages about how inspired you were, asking about how it was made, and eagerly waiting for what I put out next. It has exceeded all of my expectations, and I'm extremely grateful to you all for turning me into something of a micro-celebrity!

I am happy to announce that work is starting on the next Sketchasaur entry. As I've said in the main post, I had a blast making this, and the concept alone was fun enough that I realized I had to explore it further. I have a few drafts for what future shorts can include, and I'm certainly open to suggestions to improve the style or scientific representations. The future is certainly looking bright for this little desk.

Speaking of which, to tide you over while waiting for the next short, I thought it would be fun to show you some of the tools and effort that went into realizing this.

While I had been developing the shaders and rendering methods for some time now (as shown by last years' shorts, I knew that, if I wanted to take the idea of a scientific illustration come-to-life to its full potential, I had to showcase it in a very different way than my previous experiments had gone. The idea of it exploring a paleoartist's drafting table seemed like a next logical step, with the animal sort of exploring what we know about it and the methods we used to find that out. Some ideas, like the 3d character's sketch lines becoming more "finalized" as a way to represent depth of field, were explored, but ultimately had to be scrapped due to the limited scope.

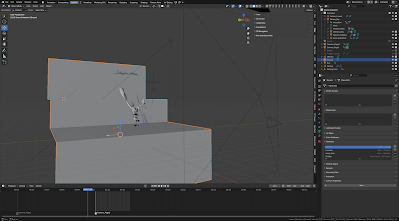

After that, I needed a desk for the character to explore. I didn't have all of the tools myself that I wanted the animal to explore, and rendering it gave me better control over the lighting and placement than I would in any desk I had in real life. Special attention was given to scale so that Blender's in-engine camera could display and react to everything as if I had shot a similar desk with my own DSLR. While the real subject of the short wouldn't be so photoreal, the effect would work best if it was exploring a believable environment.

After making sure the main set pieces like the claw and magnifying glass were in place, I took some wireframe shots to use to layout the pages.

The Deinonychus model was fairly simple; sticking with a sketchbook style meant that I only had to focus on the details I wanted to. Even so, there was a lot of effort to balance that style with the accuracy it would require as a mock-scientific illustration. The final rig had 147 bones and used Blender's highly versatile Grease Pencil suite to animate smaller details like the eyes with dynamic vectors.

The layout files were set to the camera as background images, giving me a general idea of where the deinonychus should look and wander on the page. Having a stylized character that knows that they're in a drawing gave me a lot of freedom to move him in ways that wouldn't be possible if I was adhering entirely to photorealism, as well as ways to emphasize that motion. Grease pencil was also used to create smears and motion lines to make the 12fps animation feel more fluid and natural in the final 24fps render.

This animation was then rendered as flat textures from two separate cameras to mimic the two pages it would run across. These were a much faster render in Eevee, which uses quick approximations to show the result almost in real time (although it was slightly slower than that with my one GPU and some more complex shaders). The real time eater came after applying those textures to the two pages and animating the camera. The Cycles render engine can raytrace with almost flawless accuracy, but getting that accuracy required bumping the sample count and applying denoising filters, making it take over three hundred times longer to rasterize than the dinosaur.

...Okay, it only took six hours, but that was still a long time to anxiously wait for the final result!

Sound design is something I have much less experience in than animation, so, while I knew it was much less important than other aspects of the project, it was certainly the area where I had the lowest expectations. I also made the music myself in Musescore 4: a simple enough composition with some strings, a marimba, clarinet, and flute to set a playful-yet-mysterious tone. In lieu of a proper dinosaur, its noises were simply me making random noises into my microphone and applying some basic pitch filters. A narration was written and recorded (also by yours truly), but was omitted to maintain the tone due to time and to avoid conflicting with the rest of the sound mix.

Overall, though, I'm very glad that all the pieces of this came together the way they did. As I said earlier, this was a learning experience for me, and while I wasn't able to implement everything the way I expected to, the overall vision stayed intact and was much better than the sum of its parts. Now that I know what my strengths and limits are, I have high hopes for how to make similar projects more quickly and with more pizzazz. Thank you all again for your role in my little window of internet stardom!

For art!

For Science!!

FOR ADVENTURE!!!

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you very much for your thoughts! If you have questions, we will attempt to reach back to you within the next few days.