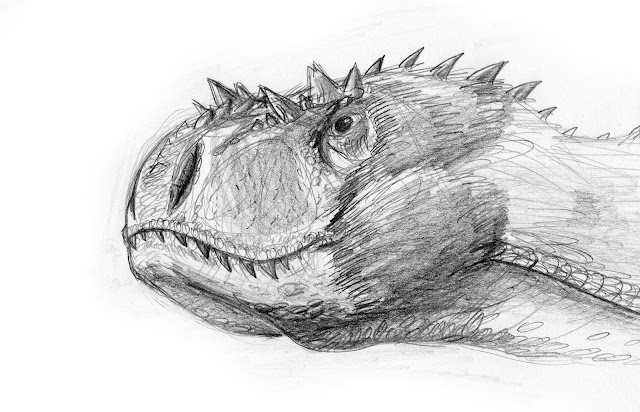

Daspletosaurus- In Your Face

Wow, this was a busy week for Paleontology. All around the world, major discoveries and announcements were made that radically changed the way we perceived these creatures. In Australia, sauropod footprints were found the size of a full-grown man, making them almost twice as big as the largest ones previously found. (Source) That's bizarre and shows us how much we have left to discover of the prehistoric world, but that's not the best bit. A study also came out that updates the way we thought dinosaurs evolved, making dinosaurs like Velociraptor and Deinocheirus more closely related to ornithischians like Triceratops and Edmontosaurus. (For the last hundred years, it was thought that they were more like the sauropods and prosauropods than anything else. Also, Source.) That is neat, but not all that surprising given the evidence for it and, therefore, a topic for a later date.

What we're here to talk about today is a fractured skull of the North American, Campanian Cretaceous Tyrannosaurid Daspletosaurus horneri. Besides being rather fractured, (See here) the fossil shows us a lot more about tyrannosaurid anatomy than we thought it could. Some parts of what we knew were reinforced, such as the mixture of smooth skin and horns across the face, but some older theories were also struck down. Last year, it was proposed that Tyrannosaurs needed massive lips to cover their teeth to keep them moisturized and strong. This skull provides more evidence against that- the area around the teeth is actually smoother than most of the rest of the face, leaving little room for any facial muscles or large scales to grab on to.

Perhaps most interesting of all is the nervous system this behemoth had. The brain was the same relative size for a tyrannosaur, but this skull shows off a massive nerve bundle towards the snout. This would have made the creature's face extremely sensitive, some estimates making it as much so as a human finger, able to detect the slightest variations in temperature and pressure.

Now comes the question- what was this nerve used for? Normally, the solution would be to see how other animals in the kingdom use similar adaptations. Crocodiles use these to detect vibrations in the water, allowing them to accurately detect a prey item's location and size in their environment. Birds have these, and it is theorized that they act as a sort of compass, letting them tell north from south and allowing for their characteristic large-scale migrations. Even mammals have them- they connect to the whiskers, giving rodents and cats a wider range of sensibility.

Of course, none of these really apply to what we know of tyrannosaurid behavior. The skull we found showed off mostly scales and horns, leaving whiskers or whisker-like feathers out of the picture. Populations were rather isolated, sticking to specific regions and territories, unlike the massive migratory patterns we see in creatures like Pachyrhinosaurus. They also spent most of their lives, if not all of them, on land, making it that much harder to sense their environment the way their archosaur relatives did. If not any of these, what purpose did this sensitive face serve?

Two major hypothesis have surfaced in the Paleontological community about this. The first one runs along with the orientation idea. If it understood its habitat well enough, it could use this 'compass' as a way to coordinate more complex hunting strategies. Some have even said that a sensitive-enough snout could detect air-pressure changes, allowing them to sense where prey is. While it's unlikely this worked over long distances, I personally do like the image of a curious adolescent dinosaur probing and prodding its snout around and on various objects to understand them better. As good an idea as it is, we simply need more data to confirm or deny it.

The other proposition, a little less appropriately, says a male-female pair would use this as a form of foreplay. Rubbing snouts together may have aroused a mating couple to get them in an... uh... "oven-baking" mood. It's probably the most mundane use, and it arguably makes the most sense. Given this, it also explains tyrannosaur fighting behavior as well. Mature tyrannosaurs have been found with deep gouges and scars in the skull, most likely from other tyrannosaurs. (Source) When asserting territorial dominance, it simply follows to attack your opponent's most sensitive spots. In the case of tyrannosaurs, this would certainly be the ultimate blow, hindering both the ability to hunt and the best chance they have of approaching a female in heat.

Much of prehistory is still a mystery, so every fossil we find is worth getting excited over- megafauna skeletons doubly so. They may never be as informative as the actual, living creature, but with the right intuition and deduction, they can end up showing so many secrets about their world. The findings this last week showed us that, yes, this is a great time to be alive for this field of study. There is a lot we know, but, as a science, there is a great deal left to learn. All I can say is that I'm excited to see what comes next and how it affects and builds off of what we know now.

Rendered in Graphite

What we're here to talk about today is a fractured skull of the North American, Campanian Cretaceous Tyrannosaurid Daspletosaurus horneri. Besides being rather fractured, (See here) the fossil shows us a lot more about tyrannosaurid anatomy than we thought it could. Some parts of what we knew were reinforced, such as the mixture of smooth skin and horns across the face, but some older theories were also struck down. Last year, it was proposed that Tyrannosaurs needed massive lips to cover their teeth to keep them moisturized and strong. This skull provides more evidence against that- the area around the teeth is actually smoother than most of the rest of the face, leaving little room for any facial muscles or large scales to grab on to.

Perhaps most interesting of all is the nervous system this behemoth had. The brain was the same relative size for a tyrannosaur, but this skull shows off a massive nerve bundle towards the snout. This would have made the creature's face extremely sensitive, some estimates making it as much so as a human finger, able to detect the slightest variations in temperature and pressure.

Now comes the question- what was this nerve used for? Normally, the solution would be to see how other animals in the kingdom use similar adaptations. Crocodiles use these to detect vibrations in the water, allowing them to accurately detect a prey item's location and size in their environment. Birds have these, and it is theorized that they act as a sort of compass, letting them tell north from south and allowing for their characteristic large-scale migrations. Even mammals have them- they connect to the whiskers, giving rodents and cats a wider range of sensibility.

Of course, none of these really apply to what we know of tyrannosaurid behavior. The skull we found showed off mostly scales and horns, leaving whiskers or whisker-like feathers out of the picture. Populations were rather isolated, sticking to specific regions and territories, unlike the massive migratory patterns we see in creatures like Pachyrhinosaurus. They also spent most of their lives, if not all of them, on land, making it that much harder to sense their environment the way their archosaur relatives did. If not any of these, what purpose did this sensitive face serve?

Two major hypothesis have surfaced in the Paleontological community about this. The first one runs along with the orientation idea. If it understood its habitat well enough, it could use this 'compass' as a way to coordinate more complex hunting strategies. Some have even said that a sensitive-enough snout could detect air-pressure changes, allowing them to sense where prey is. While it's unlikely this worked over long distances, I personally do like the image of a curious adolescent dinosaur probing and prodding its snout around and on various objects to understand them better. As good an idea as it is, we simply need more data to confirm or deny it.

The other proposition, a little less appropriately, says a male-female pair would use this as a form of foreplay. Rubbing snouts together may have aroused a mating couple to get them in an... uh... "oven-baking" mood. It's probably the most mundane use, and it arguably makes the most sense. Given this, it also explains tyrannosaur fighting behavior as well. Mature tyrannosaurs have been found with deep gouges and scars in the skull, most likely from other tyrannosaurs. (Source) When asserting territorial dominance, it simply follows to attack your opponent's most sensitive spots. In the case of tyrannosaurs, this would certainly be the ultimate blow, hindering both the ability to hunt and the best chance they have of approaching a female in heat.

Much of prehistory is still a mystery, so every fossil we find is worth getting excited over- megafauna skeletons doubly so. They may never be as informative as the actual, living creature, but with the right intuition and deduction, they can end up showing so many secrets about their world. The findings this last week showed us that, yes, this is a great time to be alive for this field of study. There is a lot we know, but, as a science, there is a great deal left to learn. All I can say is that I'm excited to see what comes next and how it affects and builds off of what we know now.

Rendered in Graphite

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you very much for your thoughts! If you have questions, we will attempt to reach back to you within the next few days.